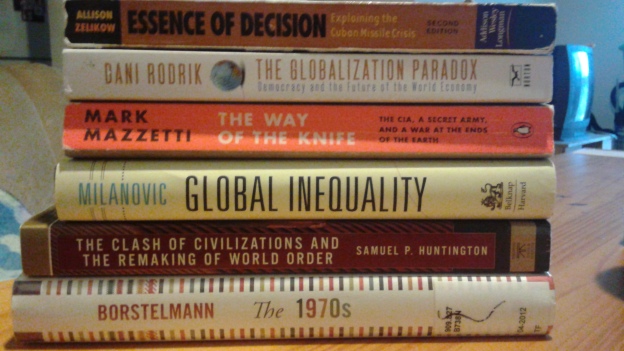

I present my favorite reads of 2016. Since I only read 4 books released last year, I will simply include in my list books that I read. In total, I finished 34 books and started many more.

6: The Way of the Knife:: the CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth (2013) Mark Mazzetti, reporter for The New York Times

This book, by Pulitzer-prize winning Mark Mazzetti, has astonishing anecdotes, literally, on every page. I had my nephew pick a number from page one through 327 and voila – “two hundred” he says. “OSS founder William Donovan was so despondent that President Truman had not named him the first director of central intelligence he decided to set up an intelligence operation of his own. During business trips to Europe he collected information about Soviet activities from American ambassadors and journalists and scouted for possible undercover agents.” When President Truman was made aware of such private shenanigans, he was mad, “calling him a prying S.O.B.” One example from one random page, and it is a good one. I read this book along the way of researching for my final analysis of President Obama’s counterterrorism (CT) policy and the most pertinent quote from the president himself was: “The C.I.A. gets what it wants.” My question is: what president has skirted the power of CIA the most? A muckraking funny-if-it-wasn’t- true expose on the CIA. One con would be that it’s anecdote heavy and hard to pull together a comprehensive understanding of the complex-nature of Intelligence work, the CIA, and the various actors, individuals and states.

5: Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (2016)

Branko Milanovic, Senior Scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study Center

A fresh, updated accounting on what we know about macroeconomics and what this portends for the future. Milanovic, reforms a classic theoretical understanding of inequality – the Kuznets curve – and coins the Kuznets wave. Succinctly put, inequality rises as economies develop yet the curve flattens out as education, for example spreads. Milanovic adds more lines to the curve and argues that inequality starts to increase once again in developed countries for various reasons, such as high-skilled and information-based job growth. This book is about (1) the rise of the global middle class; (2) the stagnation of the developed world’s middle class; (3) the rise of the global 1%. His prediction is gloomy: we will most likely see increased inequality because the current global climate to tackle this problem is wanting and the task arduous and global governance is limited. “Social separatism” is increasing and this portends a precarious future in our ever-globalizing world.

4: The 1970s: A New Global History from Civil Rights to Economic Inequality (2012)

Thomas Borstelmann, a Distinguished Professor of Modern World History at the University of Lincoln-Nebraska

I keep trying to formulate exactly when much of the world took a right-wing authoritarianism and extreme form; look at photos of Afghanistan in the 1950s-1960s for an example of what I’m conjuring up. I keep getting to 1979. Well, before said year the 1970s was a fascinating decade that so many positive strides regarding civil rights for black Americans and also women. Income inequality started rising precipitously for the developed world in the middle of the decade and the first Islamic revolution of the modern era happened, when the Shah in Iran was overthrown by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. This global history, which really is American-centric, is a fantastic read. I think about this book all of the time. For readers of contemporary history, this is a good one that I stumbled upon while perusing the “sale” section at my local library.

3: The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy (2011)

Dani Rodrik, the Rafiq Hariri Professor of International Political Economy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University

We read this book in my proseminar in globalization and out of the ten books we read, this book warranted the most discussion and “thumps up” bar none. Rodrik brilliantly excoriates, at times but with minimal vitriol – his fellow economists and their religious adherence to the Washington Consensus. He provides data to support his argument that some sort of embedded liberalism or a updated version of Bretton Woods is the most secure, fair, popular, and effective way for states to enter the developed strata of states. It’s in this book that he presents the trillemma: you can pick two, but only two. We can either live in a world of deep globalization and democracy; deep globalization and global governance; or global governance and democracy. Rodrik inclines

2: Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis: Second Edition (1999)

Graham Allison, Philip Zelikow, John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and Department of History at University of Virginia, respectively

This essential read for IR students is one I am grateful was assigned; I used the Rational Actor Model and the Governmental Politics model to compare the president’s counterterrorism policy for my capstone research paper. Along with Organizational Structure Model, these 3 frameworks are theoretical kingpins. The case study analyzed was the Cuban Missile Crisis and it was brilliantly done. Essence became the bedrock textbook and the impetus for opening the JFK School of Government at Harvard. If you want to know exactly how the insider process happens, and the complexity and complications of hundreds (now thousands) of actors involved in decisions, this is a great start. A foundational IR text from a heavyweight scholar, Allison, who has since penned many more books that are worth reading.

1: The Clash of Civilization and the Remaking of Global Order (1996)

Samuel P. Huntington, co-founder of Foreign Policy; Professor at Harvard; president of the American Political Science Association (APSA)

I’m linking to my blog post where I opined my feelings of this work. Seminal work here.

Best book released in 2016

Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror

Michael Hayden, former head of the CIA, NSA, and intelligence of the Air Force

Hayden has worked in the U.S. Intelligence community for decades and his part-memoir and part-current affairs review of the world we live in was my favorite memoir I read this year. For an intelligence official, the work was deeply honest, fair, and wide-ranging. The impression you get is of a big mind with big ideas and even bigger secrets; at once, a patriot who wishes he could tell Americans more but he can’t, for their security. I have been going through government official memoirs – I’ve only read a few so far – and this might be my favorite, though Chollet’s and Brooks’ are close. (I haven’t finished Brooks’ yet therefore it can’t be on this list but it’s damn good.)

I’m looking forward to reading so many more works next year – I hope to even finish listening to Moby-Dick!