My favorite week of the year is #listweek. I love reading people’s lists of favorite books, music, articles/essays, and movies. Though I rarely watch movies, so you won’t likely find me making a list of them, I do read a lot. These are my favorite books of the year.

5. Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero (2019),

by Tyler Cowen (St. Martin’s Press)

Readers of Tyler Cowen know that his books tend to be quite different than what the title often suggests. This book, however, is Cowen’s most straight forward. In it, he defends big business and U.S. multinational corporations, which have always been a bain of existence for the left; and which have also come to face scathing criticism of some sectors of the right as of late, including from Senator Marco Rubio and Fox News pundit Tucker Carlson. In this populist age, Cowen found it the right time to take a close look at the largest players in the private sector to really see if in fact, they deserve the scorn they so often receive. Cowen admits in a podcast interview that readers could actually come away with divergent opinions about where to go from here: sure, the intuitive reading could be to leave these Goliaths alone, they are doing what we asked them too – lower prices, increasing quality, and following consumer demand. However, the counterintuitive could be “these companies because they are strong, could actually face greater regulation and still produce what we want.”

I recommend this book as a good introduction to Tyler. I’ve read many of his other works, one changed my life and my self-understanding (The Age of the Infovore), but this book is the easiest to follow; it’s an exciting read since it challenges so much of my priors. Readers of the left should read this. It’s also not a puppy dog love-letter; there are negative findings regarding some sectors of the private sector, including health care, for example. Health care faces “the single greatest market concentration issue in the U.S. today, and I think the critics are on the right track here,” Cowen writes (91). One creepy acknowledgment and a strange one coming from a libertarian-ish thinker is one that comes from the section where he talks about the coming Internet of Things when all our appliances will be connected to the Internet. He writes:

“When that rueful day comes, I’m going to be more careful about what I say, even in the confines of my own home. Perhaps especially in the confines of my own home, where it is going to be fairly clear who the main speaker is” (125). I will never be careful as to what I say in my own home.

Cowen actually sketches out a theory as to why we hate business the way we do: we personalize it; it’s human nature to do so, and we don’t think about comparing it’s successes and promises and achievements against other industries or people in our own lives. He writes that we should be far more worried about our family and friends lying to us and betraying us than these global Goliaths. A provocative (but not gratuitously so) and really fun read, actually.

4. Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age (2019),

by Bear F. Braumueller (Oxford University Press)

Bear F. Braumueller, at The Ohio State University wrote one of my favorite international relations (IR) books I’ve ever read. I’ve dug into the “decline of war” literature and found most of the quantitative works wanting, at best; and disingenuous and alarming at worst. This is a long, arduous and complicated debate but I can give a few sentences on the descriptive consensus. After two devastating world wars, interstate war has been declining; and in particular, interstate war has been declining and rapidly so since the end of the Cold War (1990-onwards). We are still plagued with intrastate war (civil wars) and terrorism, but not interstate war. The three big claims of the “decline of war” literature are that the rate of war initiation, the deadliness of war, and the conditions that are the most likely causes of war have all decreased in a systematic way. However, Professor Braumueller reassesses the data, and models that IR scholars use and his findings and techniques deserve serious attention.

The professor finds these three above claims as largely, though not entirely, baseless. He does so, with a team of researchers, by replicating many “decline of war” quantitative papers from the top journals from the last decade. His three most salient points are as follows. First, there is no “general downward trend in the incidence of the deadliness of warfare.” Much of the decline of the deadliness of war comes from the decision to use the global population as the denominator which is stupendously misleading, as it assumes that every person on earth has an equal chance of dying in any war, regardless of location. This is the formulation that Pinker (2011; 2018) uses, for example. Second, at least until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, Braumoeller shows using technique after technique, model after model, that since 1815 through the end of the Cold War, even if you take out the two world wars, the rate of initiation of war has actually quadrupled, or increased by four. So yes, interstate wars have been declining for maybe 30 years or so. But, we would need another century of no great wars between nation-states for this to actually become a trend. Finally, myriad factors have been discovered as causing war: geographical and land disputes; trade disputes, personality or psychological factors; regime-type; alliance commitments, and so forth. The findings show that some of the potency of some of the variables have declined while others have increased or showed no statistically significant pattern.

I could talk about this book all day long. My above summary only scratches the surface. The author gets into different world orders; finds that the deadliness of war follows a “power law”; and explicates why it’s a fallacy to assume the effect of a given variable is constant over time. This last point for IR students is important. As he notes, “students of international conflict who use statistical methods will probably be horrified by these results. They should be. Nearly all statistical studies of international conflict use methods that assume the effect of a given variable is constant over time. That assumption is so wrong, so often, that it should probably be considered incorrect unless proven otherwise” (174).

This is a must-read for IR students, or for global politics nerds, in general.

3. Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism (1997),

by Michael W. Doyle (W.W. Norton)

I read this book over the summer leading up to my master’s exams. I can’t quite remember what sparked me to finally read this book but I was absolutely blown away at is comprehensive and learned understanding of international relations. IR textbooks are actually quite good; however, I’ve read no better book that encapsulates that state of the field’s leading theoretical contributions than this book, released over 20 years ago. It also acts as a compendium of resources; it has extensive footnotes and a great bibliography. The next time I have a student come into my office asking for an international relations book recommendation (last time I recommended A World in Disarray (2017) by Richard Haass) it will be this book.

As a professor, I anticipate pulling from this book quite frequently. Textbooks mention classic thinkers like Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau, Marx, and Kant, for example; Doyle actually summarizes quite succinctly and uses passages from the above thinkers in smart ways to expose the context of the arguments.

This book is great and will be an indispensable resource for decades to come.

2. A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, by Adam Gopnik (Basic Books)

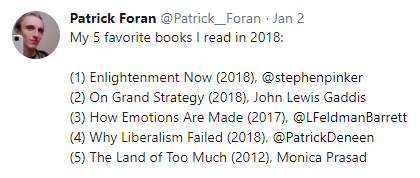

Last year I read Why Liberalism Failed (2017) by Patrick Deenen and it became my favorite contemporary work of political philosophy. This year Adam Gopnik’s beautifully written exploration of what exactly liberalism is, easily became my new favorite contemporary work making an explicit argument for liberalism. As readers of The New Yorker know Gopnik is an exquisitely beautiful writer. This book illustrates that.

The style of the book is twofold. It first opens with Gopnik telling the reader that while on a walk with his daughter in the early morning hours after Trump won the US presidency in 2016, he was struck that he wasn’t able to articulate the importance of liberal democracy. He then realized he had a book to write; first to his daughter, Olivia; then to all of us. So throughout the book Gopnik speaks to Olivia. Second, Gopnik directly and earnestly engages in the best arguments against liberalism (ch. 2: Why the Right Hates Liberalism; ch. 3: Why the Left Hates Liberalism). This method allows Gopnik to make his argument in favor of liberalism that much stronger.

What is liberalism? It is “the most singular spiritual episode in all of human history,” Gopnik muses (18). Ok, more on that in a minute. What else is it? “ Liberalism is an evolving political practice that makes the case for the necessity and possibility of (imperfectly) egalitarian social reform and greater (if not absolute) tolerance of human difference through reasoned and (mostly) unimpeded conversation, demonstration, and debate” (23-24). This is a somewhat dry definition but it is what Gopnik does to bring this idea, value-system, discovery to life that gives this book its beauty and power. Later Gopnik argues that “liberalism isn’t a political theory applied to life. It’s what we know about life applied to a political theory” (238). I find this aphorism true.

For thousands of years, we have tried to understand what makes a human being well…a human being. We are a higher-order mammal with transcendental dreams and experiences. We are an evolved species that has been incredibly successful because we create and spread culture; we are capable of absolute beauty, innovation, and amazing levels of cooperation; yet are also capable of absolute tyranny, destruction, and zero-sum competition. The social-political system that best allows us to keep discovering what we really are, psychologically, artistically, biologically, spiritually, interpersonally and so forth, is a liberal one. “The special virtue of freedom is not that it makes you richer and more powerful but that it gives you more time to understand what it means to be alive,” writes Gopnik (238).

Liberal values include skepticism, constant inquiry, fallibilism, and self-doubt. These values actually produce the space for richer non-material, inner and outer lives. This brings us back to claim that liberalism is a spiritual endeavor. How so? “All of these consequences of these values seem ‘merely’ material, but they are what enable us to live a richer life, accept our mortality, and find the path to unselfish attainment. They allow us to pass on a better world to our children—to spend every day with better music, more poetry, better food, better wine grown in more places. To make love with whom we want instead of with whom we’re ordered. These are positive values. And to those who don’t find them satisfying we say: go, choose your own” (231-232). Beautiful. A commitment to pluralism is the glue here.

This book is a reminder to not take the civilization we have for granted. Like Carl Sagan said about science working so well that it allows us to underappreciate and to take for granted the modern application of science allowing us to live happy, comfortable lives, by way of indoor plumbing, electricity, indoor heating and cooling, 24/7 wifi Internet, and the internal combustion engine; liberalism and liberal political systems allow us to discover who and what we are; it allows us the space necessary to adapt, make mistakes, build families of our choosing (or not). The time is now for these reminders.

Gopnik’s book A Thousand Small Sanities is one of my favorites of the year and of all time.

1. How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (2019), by Daniel Immerwahr (Macmillan)

This book is my favorite of the year; it’s one of those books that you can randomly read a sentence, or paragraph, and think about or discuss in context or out of context for hours.

This is a remarkable history of what Immerwahr calls “the Greater United States,” the parts of the U.S. that are obscured and obfuscated about: the fact that for nearly half of century, the U.S. occupied, controlled, and in its own idiosyncratic way, was a colonial, imperial power over. This is a history of how the U.S. acquired Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, Wake, the Bikini Atoll, Guam and so many more territories (94 islands in the Caribbean alone, mostly to mine guano), including now states Hawai’i and Alaska (established in 1959). Including occupied countries after World War II (WWII), “the Greater United States included some 135 million people living outside the mainland” (17). More than 12.5% of the Greater U.S. population leading up to WWII was outside the states, which is a larger percentage than black Americans. The historian notes this not to compare lives and repressions, but to illustrate this massive part of the Greater United States that most U.S. citizens know nothing or very little about.

Some of these colonies/territories fought long battles to become independent (Philippines, became independent from the U.S. in 1946; the Panama Canal Zone in 1979). Others, such as Puerto Ricans, U.S. Virgin Islanders, Guamanians, American Samoans are considered citizens but only by statutory; this status can be revoked. These “unincorporated territories” or commonwealths are treated unequally and the people are treated as second-class citizens with partial rights and representation. Peurto Rican “citizens” can vote in primary elections but not in general elections, for example; Medicaid on the island is less generous but facilities must meet the same standards of care as the mainland, for another example (US News 2018).

This book is lively with larger-than-life characters and inventions all used as examples to show just how you hide an empire. Some territories were used as “zones of experimentation” (2019, 158). Take Cornelius P. Rhoads, who made the cover of TIME in 1949. As we know, TIME often features stories on important people, even if they are notorious or despicable figures. Rhoads is not often used as such an illustration. He should be.

Rhoads, trained at Harvard, was a physician who was deeply racist. Through the Rockefeller Anemia Commission, he experimented on Puerto Ricans, without them knowing; giving some treatment for anemia, while letting others suffer, for example. He wrote in a letter that Peurto Ricans were “the most dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere,…they are even lower than Italians.” (TIME actually published this letter but omitted the above part). Rhoads was also the chief of the Chemical Warfare Service, a part of the U.S. Army founded during World War I. He was part of the team that implemented “jungle tests,” experiments with chemical weapons (293). Rhoads was indeed a prominent and leading cancer researcher and his reputation on the mainland was high. To Peurto Ricans, he was a villain. Immerwahr highlights that the American Association for Cancer Research gave a reward for over 20 years named after Rhoads. How so? A hidden empire is an answer. The donor who gave the award had no clue of Rhoads’ history in Peurto Rico until a biologist from the University of Peurto Rico filed a complaint.

There are fascinating chapters on guano and guano mining (ch. 3), the hundreds of military bases the U.S. has around the world (ch. 21), and how the synthetic revolution (in rubber, fertilizer) and globalization (international weights and measurement standards) helped the U.S. liquidate its holdings and to shed overseas territories (chs. 16, 17, 18). Immerwahr explores the spread of English and the red octagon stop sign as forms of U.S. soft power. This book has everything. He explores the origin stories of Gojira/Godzilla, the James Bond movie franchise, the Beatles and so much more – and how so much of popular culture was inspired by and/or constituted directly from the expanding U.S. influence.

How to Hide an Empire (2019) is one of the best books I’ve ever read. Period.